Article and Figures Provided By: Trevor Joyce and Jefferson Hinke

Co-Principle Investigator: Trevor Joyce – NOAA/SWFSC Affiliate Environmental Assessment Services, Inc.

Co-Principle Investigator: Jefferson Hinke – Southwest Fisheries Science Center/ Antarctic Ecosystem Research Division (SWFSC/AERD)

A key mission of the Antarctic Ecosystem Research Division (AERD) at NOAA Fisheries’ Southwest Fisheries Science Center (SWFSC) is to develop an understanding of how an international krill fishery operating in Antarctic waters may impact other Antarctic wildlife that consume the main target of this fishery: Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba). Three species of brush-tailed penguins (Pygocelis spp.) nesting in the South Shetland Islands off the Antarctic Peninsula primarily or exclusively consume Antarctic krill (Figure 1). Over the last three decades AERD scientists have monitored the number of penguin chicks raised each year by Adelie (Pygocelis adeliae), Gentoo (Pygocelis papua), and Chinstrap (Pygocelis antarcticus) penguin as one important indicator of how these populations are responding to natural variability and to the impacts of the krill fishery.

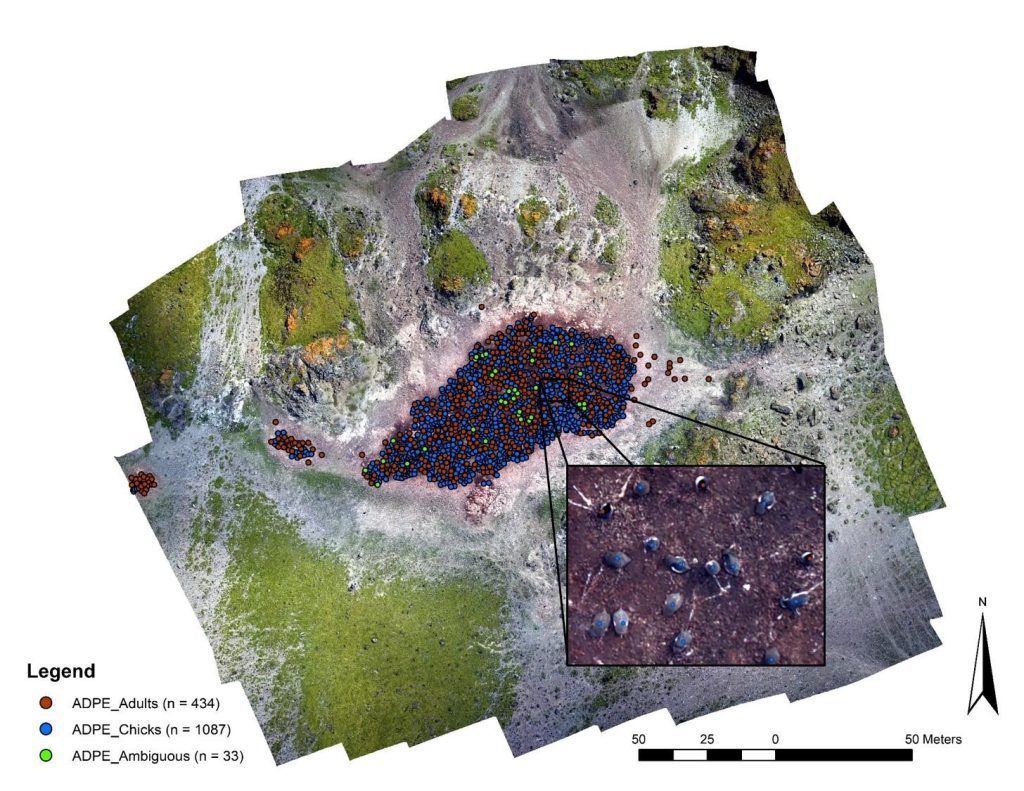

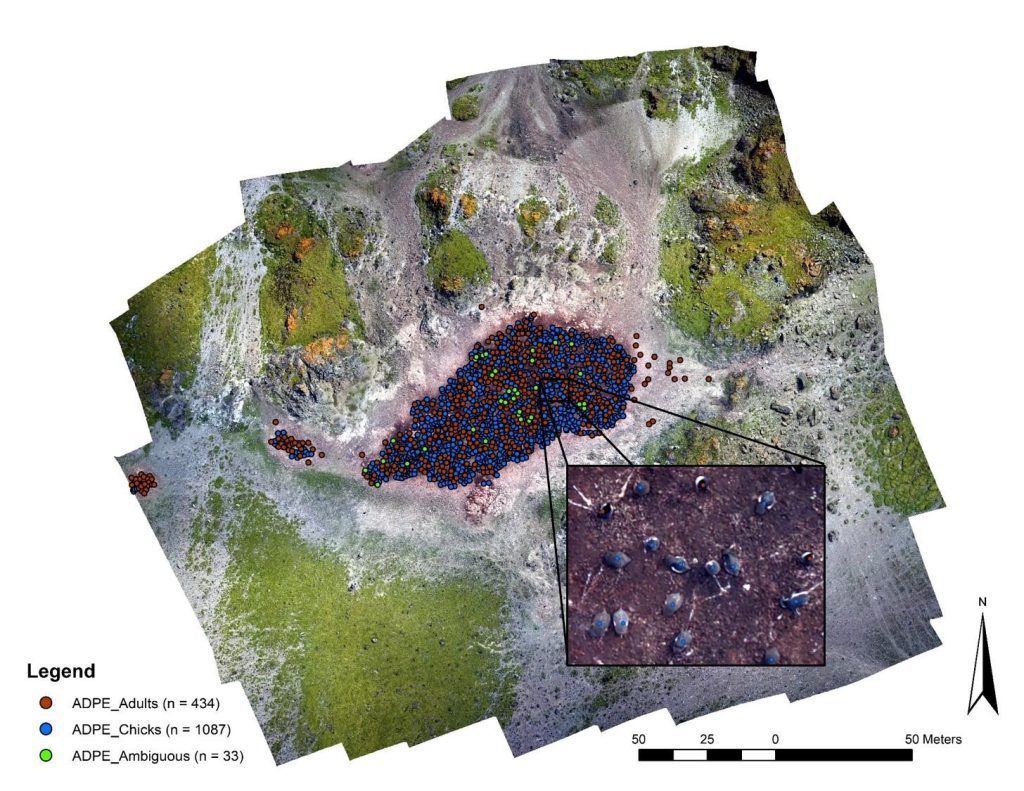

During this project Dr. Trevor Joyce, a contractor affiliated with the SWFSC’s Marine Mammal and Turtle Division, and Dr. Jefferson Hinke from AERD flew a series of Uncrewed Aerial Systems (UAS) missions at AERD’s Copacabana Field Camp on King George Island, Antarctica (62.178°S, 58.446°W) using the FireFly6 Pro fixed-wing vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) UAS. The purpose of these flights was to collect very high-resolution aerial images (0.7-1.2 cm ground sampling resolution) of the penguin colonies in order to count the number of penguin chicks produced in the current breeding season (Figure 2). A UAS census approach has the potential to achieve more precise counts of penguin chicks compared to traditional “boots-on-the-ground” counting methods by minimizing “skipping” and “double-counting” errors that become unavoidable when manually counting large aggregations of animals. UAS flights also cause little to no disturbance of penguin colonies compared to human researchers moving through the colonies (Krause et al. 2021).

Aerial images and associated flight telemetry data collected during these flights were combined using photogrammetry software called Agisoft MetaShape, which produces “orthomosaics” stitching together numerous separate images into a coherent, spatially-referenced, high-resolution surface that overlays seamlessly on a three-dimensional terrain model (i.e., similar to GoogleEarth but at a much higher resolution). This orthomosaic surface was then used to count and map penguin chicks and adults (Figure 3). The spatially-referenced orthomosaics will also allow to precisely map colony boundaries which will serve as an important baseline to measure future shifts in colony size and distribution as breeding conditions change in the rapidly warming Antarctic Peninsula region.

During these UAS mapping operations Dr. Joyce and Dr. Hinke also flew the first Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) UAS missions conducted by NOAA Fisheries. BVLOS flights crossed the tidewater inlet of the Ecology Glacier from a ridge above the Copacabana Field Camp to map Adelie penguin colonies at Rakusa Point along the western shore of Admiralty Bay (Figure 4). This project, funded and facilitated by the NOAA Office of Marine & Aviation Operations (OMAO) Uncrewed Systems Operations Center and by the Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR) Uncrewed Systems Research to Transitions Office, will open new possibilities for conducting UAS marine wildlife surveys by more than doubling the range and increasing up to four-fold the spatial coverage that can be achieved during UAS mapping and survey missions. By increasing the spatial scale over which UAS operations can be safely conducted, BVLOS flights greatly expand the utility of UAS technology in wildlife research.